In Berlin, you can actually feel the air fossilized in its history. While one can argue about the phenomenological contradictions inherent in that, the sensation of it is undeniable. The city has seen itself as the focal point of geopolitical watersheds that have shook the foundations of human civilization in the last few centuries - blinding flashes of human achievement, alongside some of the darkest moments of human history. Keeping aside the subjective judgments on these historically gargantuan episodes, Berlin has been "the time" and "the place" of immense significance, many times over.

I had heard that the Germans loved their beer. But their newfound pride in their wine was news to me. Therefore, although I found it strange to be having the grape brew one evening in Berlin, Professor I. F. was a man of very specific tastes - namely vino rojo. Sitting on the window ledge of a spacious apartment in Wedding, we had been mumbling through the didactics and reveries of many of the titans of thought that have called this city home - Marx, Einstein, Heiddeger, Nietzsche.

Whenever the Professor and I meet in conversation, "reality" is always an elusive concept for the both of us. Our games of words are inherently rooted in our flimsy attachments to "truth". I daresay, maybe even our friendship, throughout the years, has depended on it.

"What you are ignoring here Farhan is that you cannot isolate yourself from the existent reality of the universe that you seem to hold so dear. That is, without you, it does not necessarily exist." The professor was responding to my "psychedelics could save the species" argument. "If you are claiming that the psychedelic experience is in fact bringing people into a recognition of a higher dimensional reality, and that such recognition makes one more empathetic to the fate of the world and the species etc. etc. etc., you seem to forget the very essence of the teaching that Nietzsche left behind for us - that IT IS ALL EPISTEMOLOGY. The foundational basis of his thought had already taken into consideration that Descartes (with his 'I think therefore I am') had it grievously wrong. For Nietzsche, there need not be the 'I' at all. There was only the thought itself."

I had assumed that his argument was reiterating the same retaliation about this topic I had heard from many others before. "You mean to say that since I cannot isolate myself from the experience, that it is solely in my perception of it? That it is all in my mind?"

"Well yeah, sort of." he said casually. I was a little hurt for being misunderstood (because to me it always felt distinctly like another mind). He could tell I was hurt. And I could tell he could tell. Because he now had a warm smile on his face. He continued "But its not a phenomenon of the psychedelic experience alone. What I mean to say is that the phenomenon of experience itself, is nothing but an epistemological exercise. I am not knocking on the psychedelics per se. What I am knocking on is reality itself."

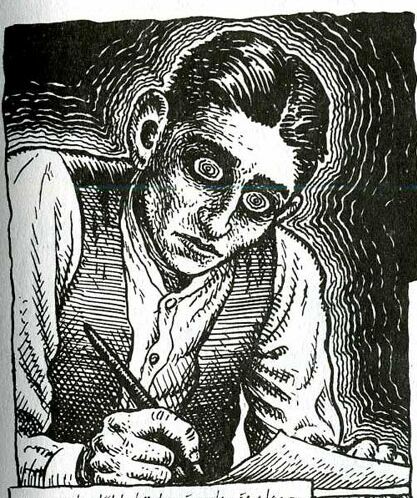

By that, it seemed, we had understood each other perfectly. It was then that suddenly, the professor shared with me (maybe even reiterated) an interesting story about Kafka. "I don't know if I ever told you about this dream that Kafka once had." The professor looked reminiscent in his expression. "He had dreamt that everyone -all his friends, family, acquaintances, and literally everyone in the world - all knew a secret about Kafka, that he did not know. In his dream, he had the clear recognition that everyone was in on something, that it was about him, and he had no idea what it was."

He then takes his heavy pause, pregnant with anticipation, inviting the question. "So, what was the secret?" I asked. The professor drew closer, and whispered, "The secret, which Kafka realizes himself by the end of his dream, is that Kafka did not exist!" Yet again, the clear image of the Ouroboros appeared in my mind.

I needed a few seconds for it to sink in completely. However, he quickly drew back and resumed, "But the funny thing is, I can't be sure if Kafka ever wrote that down, or whether I have completely made this up!" He could read my confusion about this. "Because, at some point I was sure that this story did indeed exist. But I have never been able to find it. And believe me, I have looked far and wide."

Professor I. F. was a Harvard PhD in German Literature. Having known him for all these years, and his assiduous dedication to rigorous research, I am inclined to say that if he has not found the story by Kafka, it is very likely that it does not exist at all.

There was now a curious and humorous silence between us. The warm smile now rested on my lips. I chuckled as I said, "Well Ian, it seems like maybe Kafka did not have the dream after all. But maybe, instead, the dream had Kafka. While you find yourself in the position of the epistemological vessel that carries the dream."

The professor listened with care. But I could tell, that deep down, he still imagined that someday he will find that story, and be able to put it to silent rest. Until then, it would keep racing on in his mind, or mine, or Kafka's - it didn't seem to matter.

I had heard that the Germans loved their beer. But their newfound pride in their wine was news to me. Therefore, although I found it strange to be having the grape brew one evening in Berlin, Professor I. F. was a man of very specific tastes - namely vino rojo. Sitting on the window ledge of a spacious apartment in Wedding, we had been mumbling through the didactics and reveries of many of the titans of thought that have called this city home - Marx, Einstein, Heiddeger, Nietzsche.

Whenever the Professor and I meet in conversation, "reality" is always an elusive concept for the both of us. Our games of words are inherently rooted in our flimsy attachments to "truth". I daresay, maybe even our friendship, throughout the years, has depended on it.

"What you are ignoring here Farhan is that you cannot isolate yourself from the existent reality of the universe that you seem to hold so dear. That is, without you, it does not necessarily exist." The professor was responding to my "psychedelics could save the species" argument. "If you are claiming that the psychedelic experience is in fact bringing people into a recognition of a higher dimensional reality, and that such recognition makes one more empathetic to the fate of the world and the species etc. etc. etc., you seem to forget the very essence of the teaching that Nietzsche left behind for us - that IT IS ALL EPISTEMOLOGY. The foundational basis of his thought had already taken into consideration that Descartes (with his 'I think therefore I am') had it grievously wrong. For Nietzsche, there need not be the 'I' at all. There was only the thought itself."

I had assumed that his argument was reiterating the same retaliation about this topic I had heard from many others before. "You mean to say that since I cannot isolate myself from the experience, that it is solely in my perception of it? That it is all in my mind?"

"Well yeah, sort of." he said casually. I was a little hurt for being misunderstood (because to me it always felt distinctly like another mind). He could tell I was hurt. And I could tell he could tell. Because he now had a warm smile on his face. He continued "But its not a phenomenon of the psychedelic experience alone. What I mean to say is that the phenomenon of experience itself, is nothing but an epistemological exercise. I am not knocking on the psychedelics per se. What I am knocking on is reality itself."

By that, it seemed, we had understood each other perfectly. It was then that suddenly, the professor shared with me (maybe even reiterated) an interesting story about Kafka. "I don't know if I ever told you about this dream that Kafka once had." The professor looked reminiscent in his expression. "He had dreamt that everyone -all his friends, family, acquaintances, and literally everyone in the world - all knew a secret about Kafka, that he did not know. In his dream, he had the clear recognition that everyone was in on something, that it was about him, and he had no idea what it was."

He then takes his heavy pause, pregnant with anticipation, inviting the question. "So, what was the secret?" I asked. The professor drew closer, and whispered, "The secret, which Kafka realizes himself by the end of his dream, is that Kafka did not exist!" Yet again, the clear image of the Ouroboros appeared in my mind.

I needed a few seconds for it to sink in completely. However, he quickly drew back and resumed, "But the funny thing is, I can't be sure if Kafka ever wrote that down, or whether I have completely made this up!" He could read my confusion about this. "Because, at some point I was sure that this story did indeed exist. But I have never been able to find it. And believe me, I have looked far and wide."

Professor I. F. was a Harvard PhD in German Literature. Having known him for all these years, and his assiduous dedication to rigorous research, I am inclined to say that if he has not found the story by Kafka, it is very likely that it does not exist at all.

There was now a curious and humorous silence between us. The warm smile now rested on my lips. I chuckled as I said, "Well Ian, it seems like maybe Kafka did not have the dream after all. But maybe, instead, the dream had Kafka. While you find yourself in the position of the epistemological vessel that carries the dream."

The professor listened with care. But I could tell, that deep down, he still imagined that someday he will find that story, and be able to put it to silent rest. Until then, it would keep racing on in his mind, or mine, or Kafka's - it didn't seem to matter.

Comments

Post a Comment